Pakistan’s prime minister has called a halt to a Chinese-backed coal power boom, in a pivot to renewables that could inspire others in China’s orbit – if put into action.

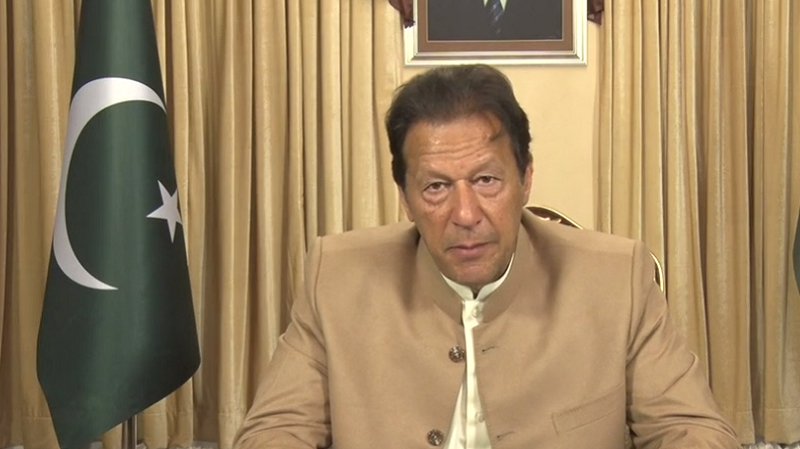

On Saturday, Imran Khan told a virtual gathering of global leaders: “We have decided we will not have any more power based on coal”.

Simon Nicholas, an energy finance analyst with Ieefa, said: “On the face of it, this is a highly significant statement for Pakistan, which was until now intending to exploit its domestic coal reserves.” The Pakistani Alliance for Climate Justice and Clean Energy (ACJCE) said the announcement was “a step in the right direction”.

Plants under construction are expected to be completed, but the announcement pours cold water on the national grid operator’s projections of a significant expansion of coal power. As recently as April, the National Transmission and Despatch Company forecast 27GW of coal power capacity would be added between 2030 and 2047, bringing the total to 38GW. “This [plan] will now need to be re-written,” Nicholas said.

Sohaib Malik, an energy analyst from Pakistan, said the discrepancy reflected a lack of coordination between government and the power sector. “There’s no integrated plan that all are supposed to follow. They work in silos more often than not,” he told Climate Home.

In the week before Khan’s announcement, Pakistan’s energy minister met the Chinese ambassador and discussed investment in renewable energy.

Chinese companies are financing or building most of Pakistan’s coal plants through the China-Pakistan economic corridor, which Ieefa called the “centrepiece” of of China’s belt and road initiative (BRI). “If coal power is being de-prioritised within the China-Pakistan economic corridor it can now happen right across the BRI,” said Nicholas.

The Chinese government has suggested it would like to make its investments abroad “greener” and its environment ministry has recently floated blacklisting coal power investments abroad.

Malaysian bank to phase out coal finance, in a victory for campaigners

Khan’s adviser on climate change, Malik Amin Aslam, told Climate Home that coal plants under construction would not be cancelled. “They have state guarantees behind their [power purchase agreements], which can’t be re-negotiated,” he said.

Aslam added: “The imported coal projects established by previous government in the middle of Pakistan’s prime agriculture belt were a criminal act of ecocide. However, owing to state guarantees, it is impossible to de-commission them without extremely heavy financial costs and these agreements are locked in for 30-year timeframes.”

According to Pakistan’s government, there are 2,640 MW of plants under construction. A 660 MW plant built by a cement company in Port Qasim is expected to be completed in March 2021 and three plants with a combined capacity of 1,980 MW should be up and running in the coal-rich Thar desert by June 2022.

Two projects have been given permits but construction has not yet started. One is a 300 MW plant in Gwadar port, which will use imported coal. The other is a 330 MW plant in Thar, which will use local coal. A handful of plants are in earlier phases of planning. Aslam did not clarify whether these would go ahead.

ACJCE called on the government to government to “halt all those coal power plants or coal mining projects which are in their initial stages of development so that these do not become an unsustainable environmental, social and financial burden for the country”.

Chris Littlecott, associate director at E3G, said that governments tended not to cancel permits as they seek to maintain “regulatory certainty” and avoid legal challenges. But, he said, developers might think “it’s not a smart move to build coal plants any longer”.

Aslam told Climate Home the government was “seriously exploring” options to close operating plants early, including a proposal by American and British think tanks to shift from coal to renewables in exchange for debt relief.

Infographic from a report by the Rocky Mountain Institute, Sierra Club and Carbon Tracker

ACJCE called on the government to hold coal plants to strict environmental standards and to “phase them out gradually because they have become non-competitive” with wind and solar energy.

In his two-minute speech at the Climate Ambition Summit, Khan said that, by 2030, 60% of all electricity produced in Pakistan will come from clean sources and 30% of all vehicles will be electric. Aslam said this would be achieved using solar, hydro and wind as well as nuclear.

Muhammad Ali Shah, the chairman of Pakistan fisher-folk forum said hydropower should not be included in the category of renewables because of its impact on river ecology, aquatic life and the lives of those dependent on river waters. Solar and wind are cheaper and more environmentally friendly, he said.

Khan said he still intended to mine Pakistan’s coal and convert it to liquid fuels, which can be used for transport, and methane gas for power generation.

Balooning debt cripples poor countries’ hopes of green recovery from Covid

Aslam said turning coal to gas or liquids has a “significantly lower carbon footprint” than burning coal. In 2009, a Duke University study found the opposite. Unless the CO2 emissions are captured, it said turning coal to gas and burning it produces more emissions than burning the coal directly.

In 2014, Laszlo Varro, head of gas, coal and power markets at the International Energy Agency said coal gasification’s “overall carbon intensity is worse [than coal mining], so it is not attractive at all from a climate change point of view”.

ACJCE’s Zain Moulvi said: “Gasification and liquefaction of indigenous coal found in Thar simply displaces the site of pollution and fails to address the wider concerns and impacts of mining in Thar which have proven to be devastating to Thari communities.”

Ieefa’s Nicholas told Climate Home this part of the plan “demonstrates the continued influence of China and the coal lobby” and a desire for energy security. Energy security could be addressed better and cheaper with wind and solar, he said.