Big polluters need to move faster to wean themselves off fossil fuels and rely less on expensive and underperforming technologies, the International Energy Agency warned in its latest net zero assessment.

The influential energy watchdog has downgraded the role of technofixes such as carbon capture and hydrogen in meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement. As their development is failing to live up to expectations – the IEA argues – countries should instead focus on the “most cost-effective” solutions, like ramping up renewables, energy efficiency and electrification.

The updated scenarios give less cover to the oil and gas industry and petrostates to promote these technologies for prolonging the use of fossil fuels.

“Removing carbon from the atmosphere is very costly. We must do everything possible to stop putting it there in the first place,” said IEA executive director Fatih Birol in a statement.

The IEA is also calling on all countries to bring forward their net zero plans.

It says rich nations should reach net zero emissions by 2045 under an “equitable pathway” that sees historical polluters take the lead. Only a handful of European countries, including Germany, are aiming to achieve that target.

Carbon capture hype

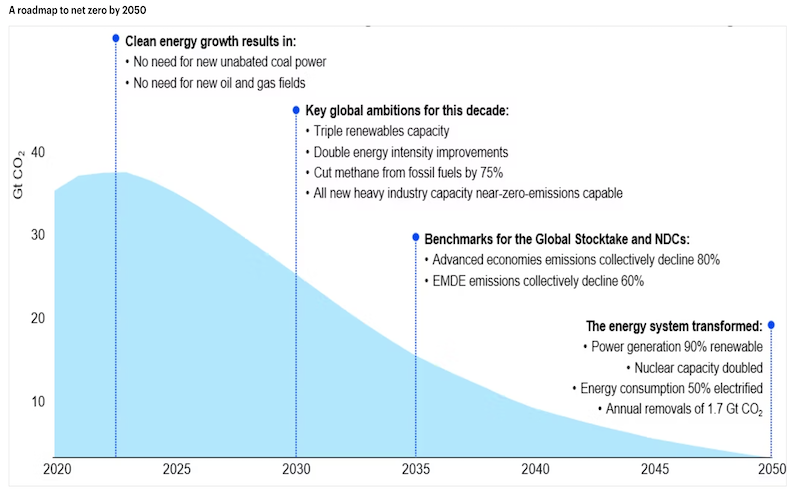

The report is the first update to the road map for the energy sector to reach net zero by 2050 debuted by the IEA in 2021. That landmark report relayed a stark message to the fossil fuel industry: development of oil, gas, and coal must stop to remain within acceptable global warming thresholds.

Since then, as discussions around the possibility of phasing out fossil fuels heated up, the sector has increasingly taken shelter behind technofixes.

Countries that produce or rely on fossil fuels particularly advocate the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) to trap their emissions, rather than ending the use of such fuels completely. This debate is expected to take centre stage at the Cop28 climate summit in November.

‘Unmet expectations’

The latest IEA assessment pours cold water on such a notion. It says the history of CCS “has largely been one of unmet expectations”, marked by slow progress and flat deployment. Only 0.1% of total annual energy sector emissions are currently captured in this way.

Catherine Abreu from the campaign group Destination Zero told Climate Home News it makes sense that models see a reduced role for these technologies. “The results of the small, tremendously expensive CCS projects that already exist make it clear that these projects are just about extracting more fossil fuels, not about cutting climate pollution,” she said.

In its new forecasts, the Paris-based agency has slashed the contribution of CCS to emission reductions in the power sector by around 40% compared to its 2021 scenario. But it can reduce or eliminate emissions in areas where other options are limited, such as heavy industries, the IEA added.

Hydrogen ‘problem’

The agency has also taken aim at hydrogen, describing it as “more of a climate problem than a climate solution” today. While demand for hydrogen has been rising, the overwhelming majority of it has been met with polluting production processes, mostly involving gas.

The IEA sees a diminished potential for hydrogen to decarbonise long-distance transport and iron and steel production, and only if it comes from “low-emission” sources such as renewables.

“Hydrogen was once considered a ‘wonderfuel’,” said Dave Jones from energy think tank Ember. “Now reality has hit home and there has been a real change in understanding of its limited uses.”

While CCS and hydrogen are underperforming expectations, the IEA keeps revising its projections for solar power and electric vehicles upwards. Cheaper renewables and stronger electrification prospects make them more appealing and viable options to reach net zero by 2050.

The IEA report comes at a time of rising tensions with oil producers. Two weeks ago Opec, the cartel of oil-producing nations, accused the agency of creating “dangerous” risks to energy security by stoking calls to end investment in fossil fuel projects.

Net zero acceleration

IEA’s Birol said “the pathway to 1.5C has narrowed in the past two years, but clean energy technologies are keeping it open”. He urged stronger international cooperation, ambition and implementation of climate plans.

While calling on all governments to raise their net zero targets, the report offers a template for differentiated responsibilities around the world.

Advanced economies take the lead and reach net zero emissions by around 2045 in the IEA scenario. Germany is the only G20 country to have pledged such a target. The United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan and Canada are all aiming to get to that level by 2050.

China should get to net zero by 2050, according to the agency, bringing its plans forward by ten years. Poorer developing economies get there “well after” 2050 in this scenario.

Thomas Hale, professor of global public policy at Oxford University, said it was important for the IEA to underline the equity implications of getting the world to net zero by 2050.

“The fundamental question of who goes fastest and who follows is a challenge at the heart of current global climate politics,” he added. “The report shows governments there is a really attractive and achievable pathway to get there.”

He expected the IEA recommendations to be considered by governments when they update their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the Paris Agreement by 2025.