Airlines could defer paying for their climate impact by up to five years, according to researchers, under an industry proposal to soften the impact of coronavirus lockdowns.

The International Air Transport Association (Iata), which represents the world’s airlines, has called on the UN body responsible for aviation to rewrite the rules for offsetting the sector’s emissions growth.

To curb the aviation sector’s growing emissions, member states of the International Civil Aviation Organisation (Icao) have agreed to make all growth in international flights carbon neutral after 2020.

With limited technical solutions available to make planes less polluting, airlines will rely on a carbon market known as Corsia. The scheme allows them to offset their emissions growth by funding carbon-cutting projects in other sectors.

The agreed baseline for measuring emissions was to be the two-year average across 2019 and 2020. However 2020 is turning into a year of anomalously low air travel, with planes grounded by travel restrictions to prevent the spread of Covid-19. That means airlines would have a bigger offsetting obligation than they anticipated if traffic rebounds quickly.

Iata is urging Icao to change the baseline to pre-pandemic levels in 2019 – a move it says could save airlines an estimated $15 billion in carbon offsetting costs.

Airlines urge UN body to ease climate goals for 2020s as traffic collapses

Last month, Iata described maintaining the 2019-2020 baseline as “an inappropriate economic burden” that would “significantly” increase the number of offsets airlines would need to buy to meet the climate target and lead to higher costs.

The proposal is to be discussed at an upcoming Icao Council meeting – a body of 36 countries, including the world’s largest plane manufacturing and airport hub nations – 8-26 June in Montreal, Canada.

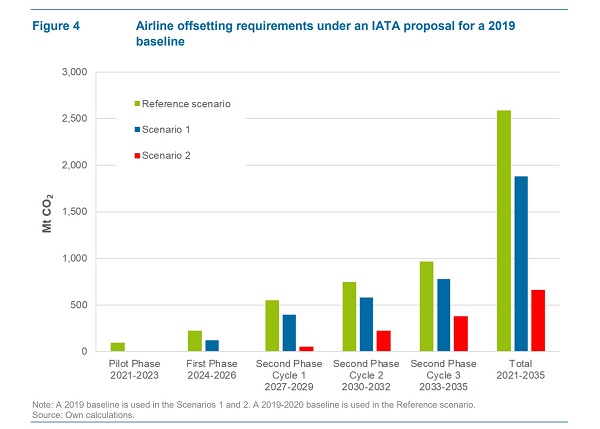

The plan would “delay airlines’ climate mitigation requirements by several years and lead to significantly fewer emission reductions,” according to Lambert Schneider, research coordinator for international climate policy at the German-based Öko-Institut, who studied the impact of Iata’s proposal on climate action.

Industry experts have argued that a lower 2019-2020 baseline would have a negligible impact on airlines’ offsetting requirements and associated costs.

On the contrary, the study by the Öko-Institut found that Iata’s proposal to increase the baseline to 2019-only emissions would reduce airlines’ obligations to offset emissions growth between 25% and 75% by 2035 – depending on the speed of air travel recovery.

Climate news in your inbox? Sign up here

Schneider and his co-author Jakob Graichen concluded that Iata’s proposal would remove incentives for the aviation sector to invest in carbon-cutting measures.

They recommended maintaining the current baseline until an Icao review planned for 2022, which is due to review the overall ambition of the Corsia scheme.

Campaigners agreed.

Annie Petsonk, aviation expert at EDF, wrote in a blog that while airlines were desperate to save money in the wake of the pandemic, hastily rewriting the rules for the sector’s emission-curbing scheme “would be penny-wise and future-foolish” and damage public confidence in Corsia.

“If investors believe that governments will make ad hoc rule changes that strand their investments, they won’t make those investments,” she said.

“Re-writing Corsia’s rules would not only give airlines a free pass to pollute for the next half-decade, it would undermine investor confidence in airlines’ climate commitments at a time when regaining investor confidence is crucial to the sector’s survival.”

Aviation’s black box: Non-disclosure agreements, closed doors and rising CO2

A coalition of NGOs including EDF, Carbon Market Watch and WWF, along with businesses and offsetting programmes have urged Icao’s Council not to change the Corsia baseline.

In a letter, they argue that consistency in apply fixed rules objectively and following established processes are crucial for investor confidence, warning against changing the rules seven months before the start of the scheme. “The lack of durable investment would contribute to worsening the climate crisis,” they wrote.

“Corsia is an important mechanism for carbon markets around the world. Changes to elements as fundamental to its design as the baseline should be treated very cautiously.”

The Öko-Institut research compares two recovery scenarios to 2035 with the climate goal airlines agreed to meet before the coronavirus outbreak.

The first is based on Icao’s most optimistic scenario which assumes a 38% decrease in air travel this year compared to pre-Covid19, a fast recovery to 2019 emissions level in the next three years and continued growth thereafter at a rate similar to what was expected before the pandemic.

The second scenario is Icao’s most pessimistic with a 71% drop in air travel in 2020, a slower recovery of more than three years and continued growth from the mid-2020s at a slightly lower rate than expected before the pandemic.

When applying a 2019-2020 baseline, the study shows that a quick recovery scenario would require airlines to purchase slightly more carbon credits than they would have if the pandemic hadn’t happened.

A built-in flexibility provision in the Corsia scheme could, however, reduce the pandemic’s impact by lowering airlines’ offset obligations during the programme’s first voluntary stage between January 2021 and the end of 2023. From 2027, offsetting obligations will become mandatory for all international flights.

Under a slower recovery scenario, airlines wouldn’t need to offset any emissions between 2021 and 2023 and would be required to buy slightly fewer carbon credits than they would have expected to before the outbreak to offset their emissions growth to 2035.

When using Iata’s proposed 2019 baseline, offsetting requirements would disappear in a quick recovery scenario until 2024 and be reduced by 25% by 2035 compared to pre-pandemic trajectory. Under a slower recovery, airlines wouldn’t have to offset emissions until 2027 – reducing mitigation efforts by 75% by 2035.

An analysis by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) published earlier this month found that Iata’s proposal could push the date for airlines to start offsetting their emissions under the Corsia scheme to 2028 or even later – 12 years after the scheme was agreed in 2016.

EDF looked at five possible post-Covid-19 scenarios for the aviation industry which assumed emissions would drop between 20% and 70% this year compared to pre-outbreak projections.

The analysis found that unless aviation’s emissions quickly rebound to levels pre-outbreak or higher by 2021, a 2019-only baseline would effectively postpone Corsia’s start planned in January 2021 for three to five years.