When news of the brutal murder of peasant leader Carlos Cabral broke on June 11, it seemed history was repeating itself in Rio Maria.

The small town in southern Pará state lies at the heart of Brazil’s most notorious, long-running and violent land struggle. In the entrance of the modest headquarters of the local Rural Workers Union, where Cabral’s funeral was held, hang the portraits of three other union leaders killed in the region.

One of the photographs is of João Canuto, a Communist Party member and Cabral’s father-in-law. He was shot dead in 1985 amid a dispute between farmers, who took over and deforested public lands illegally, and landless peasants who pushed for agrarian reform with the backing of leftist organizations.

At the time, Canuto led the Rio Maria union, the same position the 58-year-old Cabral held 34 years later when two men approached him on a motorcycle a few meters from his house. One of their .38 bullets went through his head.

Southern Pará is in a corner of the Amazon that was chaotically opened up during the 1970s military dictatorship by new roads and a big hydroelectric dam. Cattle ranchers moved in, taking public lands, as well as territories from traditional communities and indigenous peoples. Today it is one of the most deforested areas in the Amazon, almost entirely converted to pasture.

Climate news straight to your inbox? Sign up here

While the forest has dwindled, the violence has continued. Cabral had already survived a murder attempt. In 1991, while walking with his friend and union colleague Roberto Neto da Silva, he was shot in the left leg. After that, both were put under federal police protection for two years. The motive was the same that led to the killing of his father-in-law, big farmers unhappy with the push for leftist-backed agrarian reform.

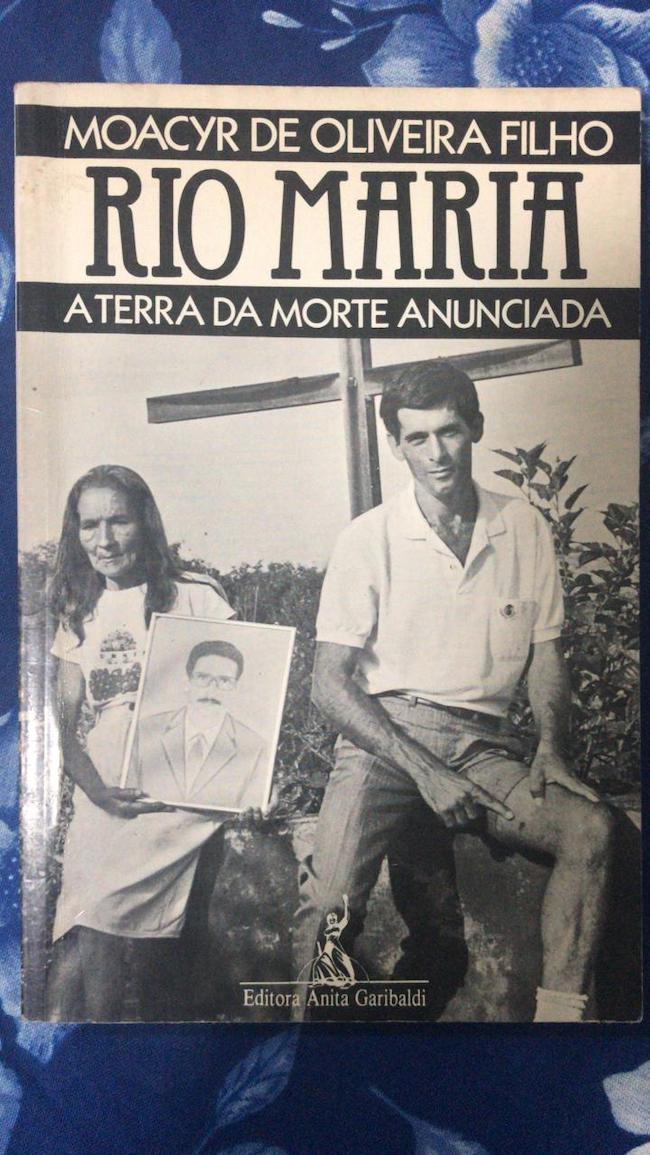

A picture of him pointing to the wound beside Canuto’s widow, Geraldina, holding Canuto’s picture became a symbol of land struggle in southern Pará.

But when he was killed, Cabral, once an affiliate of the Workers Party, was no longer promoting leftist ideals for the rural poor. Last year, during the election campaign, Cabral embraced far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro.

Cover detail from book Oliveira Filho, Moacyr de. “Rio Maria: a Terra da Morte Anunciada” [Rio Maria: the Land of Foretold Death]. Anita Garibaldi Press, 1991 (Photo: João Roberto Ripper/Imagens da Terra)

Bolsonaro has sided with big agriculturalists against peasant land reform movements, which he accuses of being terrorist organizations. Last July, during a campaign visit to the region, he paid tribute to military police tried and condemned for killing 19 rural workers in 1996.

But there is a simple explanation for Cabral’s change of allegiance: greed. Family and friends at his funeral said he had become one of the land-grabbers, stealing forest from an indigenous territory to be stripped, mostly for cattle farming.

Traditional left-leaning organizations, such as the Landless Movement and the Catholic Church-backed Pastoral Land Commission, have long opposed the theft of indigenous land. But Bolsonaro, who became president in January, has championed the reversal of indigenous land demarcations in order to accommodate white farmers and mining projects.

Cabral’s fall tells a story of chaos that threatens to envelope the Amazon and its remaining rainforests.

According to those who knew him, years ago Cabral and a brother took possession of 1,542 hectares of forest about 425 km from Rio Maria, a 12-hour drive mostly on unpaved roads. The land was publicly-owned but is now inside the Apyterewa Indigenous Territory, home of the Parakanã ethnic group.

In recent years, Cabral has traded land inside Apyterewa. A friend of the union leader told Climate Home News that last year he purchased 484 hectares from Cabral’s third wife (he is no longer married to Canuto’s daughter).

“He thought Bolsonaro would shrink the indigenous reserves,” said Cabral’s friend and survivor of the 1991 shooting Neto da Silva, 61, who opposes encroachment on indigenous territories.

Cabral ‘insisted on this stupidity’. Union member Roberto Neto da Silva in the Rio Maria union headquarters; above him, three portraits of killed union leaders (Photo: Fabiano Maisonnave)

Indigenous land rights in Brazil are backed by the constitution and in the case of Apyterewa, the supreme court. In 2015, in a final decision, it ruled that all non-indigenous people be removed from the area. The federal government has never complied with the order.

In Facebook posts, Cabral called for a military intervention to shut down the court, a campaign backed only by the most extremist forces among Bolsonaro supporters.

“I always tried to get him out of there”, said Neto da Silva, who spent the whole day in his old friend’s funeral. “But he was motivated by other interests and insisted on this stupidity, to the point he changed his view as a union leader.”

Climate Home News needs your help… We’re an independent news outlet dedicated to the most important global stories. If you can spare even a few dollars each month, it would make a huge difference to us. Our Patreon account is a safe and easy way to support our work.

Across the Amazon, a similar pattern is being repeated. Apyterewa, Uru-eu-wau-wau and Cachoeira Seca indigenous reserves all report a surge of invaders since Bolsonaro’s election.

As federal protection for these territories has been reduced, some peasants are grasping the opportunity to finally control land of their own. The indigenous landowners, many of whom were uncontacted by white culture less than 30 years ago, are powerless to fight back without government backing.

That will not come from Bolsonaro. The president has ordered his secretary for land affairs, cattle rancher Nabhan Garcia, to revise indigenous demarcations. The former head of the Ruralist Democratic Union (UDR), a far-right organisation, Garcia wants to legalise practices such as the leasing and even the selling of indigenous territories, changes that need congressional approval.

Last week, Garcia’s repeated clashes with the president of Funai (Brazil’s indigenous bureau), army general Franklimberg de Freitas, led to the firing of the latter by Bolsonaro.

Guns and ammunition seized from the men accused of killing Carlos Cabral (Photo: Supplied)

In his farewell speech to Funai officials on June 11, Freitas said “every time Garcia speaks about indigenous peoples, he salivates with hatred towards them”. He said some members of Bolsonaro’s government consider the indigenous bureau “an obstacle for national development”.

The result is that land prices have surged in Apyterewa, as more and more people see the land as a safe investment. Last year, one hectare cost as little as $53. Now, it is up to $212, explained Cabral’s friend.

But with opportunity came rivals. Cabral’s business put him on a collision course with other land-grabbers. On Sunday, Pará’s civil police arrested two farmers suspected of involvement in the killing. A third has escaped. All of them had traded land illegally inside Apyterewa, according to the police investigation.

Bolsonaro’s plan to unlock the Amazon: split its indigenous peoples

Along with the farmers, the police seized an arsenal of illegal guns and ammunition, including revolvers, pistols and rifles. The cache was so large they hadn’t finished counting when this article was written.

Between 2017 and 2018, according to government figures, Apyterewa was the fourth most deforested indigenous land in Brazil, with a loss of almost 2,000 hectares – an increase of 351% compared to 2016 and 2017.

Cabral’s funeral was attended by his friends, union members and family, including his mother. Beside the coffin, the only funeral wreath bore the message: “We are sad for the irreparable loss. Workers Party.”

We have changed our rules around republication. See here.