On 31 August 2018, then presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro fired the starting gun on a land-grabbing frenzy in the Amazon.

“Here in Rondônia we have 53 conservation areas and 25 indigenous territories. It’s crazy what is done in Brazil under the banner of the environment,” he said at a press conference in Porto Velho. “This has blocked the progress of those who want to invest in agribusiness and even in family farming. We’re going to find a way to turn this around.”

Encouraged by this and other Bolsonaro announcements, people started invading protected forests and clearing plots of land, even before the results of the election were known. Five days before the second round of the election, hundreds of families entered the national forest of Bom Futuro, in the Porto Velho municipality. The following January, with the new president already in place in Brasília, scores of men took over part of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous territory, in the municipality of Jorge Teixeira, Rondônia.

This movement has gained momentum over recent weeks. Another five state conservation units in Rondônia have been invaded: Guajará-Mirim Park, ecological station Samuel and the extractive reserves Rio Preto Jacundá, Aquariquara and Ipê.

Of these five areas, only Ipê has been vacated, after a court decision taken by request of the Rondônia state prosecutor’s office and the federal public prosecutor’s office in Rondônia, who are taking action to revert the other invasions.

Landless worker Sebastião Pereira, 70, rests in his tent in an encampment in Rio Pardo village, in Rondônia (All photos: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress)

Last month invaders camped outside the state government house in Porto Velho to demand the regularisation of plots of land in Guajará-Mirim park and its buffer zone. Monitoring provided by the national institute for space research (INPE) has shown 979 hectares of land have been illegally deforested over the last 12 months, this in an area in which the forest was practically intact.

In the Jacundá national forest, there is a threat posed by a landless encampment set up in August on one of the access roads, but no invasion has occurred as yet.

While invasions of indigenous lands and conservation areas in the Amazon region are taking place, the occupations of large agricultural estates have come to an end. There has not been a single case of this kind in Rondônia for at least four years, according to Brazil’s national institute for colonization and agrarian reform (INCRA). Under Bolsonaro, there were only five cases in 2019 and none this year.

The shift in focus also reflects a change in the main actors. In the place of social movements, such as the landless rural workers’ movement (MST) that campaigns against the invasion of conservation areas and indigenous lands, unknown and recently created associations have arrived. These associations, advised by lawyers and geo-referencing firms, with the involvement of cattle ranchers in the region, supporters of Bolsonaro, enjoy the support of local right-wing politicians.

They try to distance themselves from the traditional image of the landless rural workers, with their opposition to ranchers. One of the supporters of these movements in Rondônia is federal deputy Coronel Chrisóstomo, an army reserve officer.

A religious realignment is also taking place. The Catholic Church, which has close ties to MST and has produced historic defenders of land reform in the Amazon region, such as bishop Pedro Casaldáliga and sister Dorothy Stang, has lost ground. Meanwhile, evangelical churches are often to be found in the newly invaded areas.

Boa Esperança camp, in the the village of Rio Pardo, Rondônia

Besides Bolsonaro’s rhetoric against protected areas and the MST, another great incentive for the invasion of protected areas in Rondônia is the recent success of these efforts. In 2010, during the Lula administration, national forest Bom Futuro saw its area reduced by two thirds so as to legalise invasions that had taken place mainly in the government of his predecessor, Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

At the state level, the governor of Rondônia, military police colonel Marcos Rocha, presented a bill to the state assembly this year that aims to legalise the invasions of Jaci-Paraná, which would affect 146,000 hectares of land. Around 55% of the conservation unit has already been stripped of forest, according to INPE.

Built on land cleared by an older invasion, the Bom Futuro camp was taken down on 10 September 2019, in a military police operation, after a court order obtained by the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), the administrative arm of the ministry of environment. Around 200 families were removed.

Some of the displaced families set up camp around an abandoned schoolhouse in the neighbouring village of Rio Pardo, in the hope of being allowed to settle. When Folha was there, in August, there were around 60 families.

Their living conditions are precarious. There are two toilets in the camp, which had been without water for five days. The children, who are not in school at the moment due to the Covid-19 outbreak, used to spend five hours on a bus to travel to and from school.

José Roberto de Jesus, 47, spokesman of the Boa Esperança camp

The spokesman for the group is José Roberto de Jesus, 47, native of Bahia. He is one of the people who believed that the forest Bom Futuro would be given to landless workers – a term he avoids, using “farmers” instead. His family migrated to Rondônia in 1984, but none of them managed to acquire a piece of their own land.

Jesus, who is a father of five, works in the cacao industry, the family’s original occupation in the region of Ariquemes. He has no formal schooling, but has worked as a miner, blacksmith and charcoal worker. He says the advance of soya plantations, cattle raising and fish farming has reduced the availability of jobs, since these are activities that provide little employment.

He was not one of the leaders of the invasion, who disappeared after the complaint lodged by the public prosecutor’s office. After the eviction, his calm and articulate speech helped him gain ascendancy in the group, where he was nicknamed Pastor.

Repeating the story told by others who participated in the invasion, Jesus says he was encouraged to enter Bom Futuro because of the support given by ranchers. “It has never been my habit to invade something that belongs to others, but a unique opportunity arose and took me to that land. The ranchers put us there, as they had been fighting with the government, who took their lands and turned them into a reserve. They preferred to lose their lands to landless workers than to the government.”

Questioned about the risk of the ranchers taking the lands back if they were regularised, he responds: “We had to pay a price. We had to risk it.

“I am an evangelical. God doesn’t allow us to invade anything that belongs to someone else, but what if you’re on land belonging to the Union? Who is the Union? The Union is us – we are workers. We were living on what was rightly ours, by law. We hadn’t invaded anything belonging to anyone else.”

Jesus says he voted for Bolsonaro and that the conversion of the Flona into a settlement depends only on the government. “I don’t understand this business of the fauna [of] Bom Futuro, but we understand that it is good land. We trust in the government, and in his campaign he [Bolsonaro] said there were many reserves in Rondônia, but they were degraded.”

A tree burns in the Bom Futuro National Forest

A few weeks after the interview, Bom Futuro was invaded once more, this time by a different group. The Rondônia military police have yet to launch another repossession operation. From the start of this year to August, over 575 hectares have been deforested, according to satellite monitoring done by the MapBiomas Alerta.

“Many families were looking for a camp to stay at, in the hope of later obtaining a plot of land through the land reform process. Today this perspective is no longer there,” says the coordinator of the NGO Land of Rights, Darci Frigo, former president of the national council for human rights.

“They will settle on the margins or in places where there are indigenous people, quilombolas [members of quilombos, settlements formed centuries ago by escaped slaves], and areas of permanent protection. The tendency is to generalise invasions. It’s not that the poor are enemies of the environment. It’s that the rich, by keeping the poor living in poverty, end up creating the conditions that lead to environmental degradation. Besides the land grabbers, you have poor people who were waiting for land reform.”

About Bolsonaro, he says this: “His rhetoric attacks indigenous people, quilombolas and landless workers. It demoralises these people in the eyes of public opinion and simultaneously signals an order to support the invasions of public lands.”

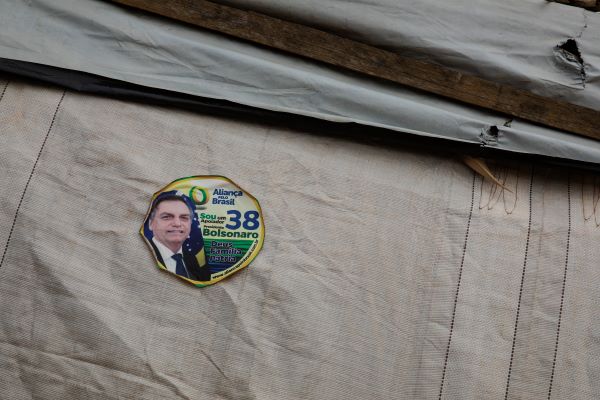

A Jair Bolsonaro sticker on the walls of a tent in the Boa Esperança camp

According to geographer Ricardo Gilson da Costa Silva, of the federal university of Rondônia, Rondônia is following the same path as Mato Grosso with the advance of soya plantations, that suffocate small farms and put pressure on the large cattle-raising operations to seek new areas. The result is further deforestation in the north of the state and the neighbouring south of the state of Amazonas.

“This means deforestation,” Silva says. He describes the recent invasions as “agro criminality.”

“It’s not a social movement. These are economic and political movements sponsored by cattle ranchers, businessmen and local politicians. They sponsor invasions of protected areas, taking along landless workers in need of land, so as to create a situation which cannot be reversed. That is what is happening in Jaci-Paraná, where the rubber tappers have been evicted and there are even airstrips now,” he said.

“It is a political and territorial project of converting environmentally protected areas into pasture land, to later turn them over to the land market and leave them for cattle raising and grain farming. It is something that has been thought out,” he says.

In Rondônia, Bolsonaro won the second round of the election with 72% of the votes, the third largest percentage in the country, only behind the states of Acre and Santa Catarina. State governor Marcos Rocha, an ally of the federal government, did not respond to comment requests.

This reporting is part of The Amazon under Bolsonaro, a collaboration between Folha De Sao Paulo and Climate Home News. Translated from the Portuguese by Clara Allain.