The UK vetoed two South American bids for cash to support rural development at a meeting of the Green Climate Fund in Cairo on Monday.

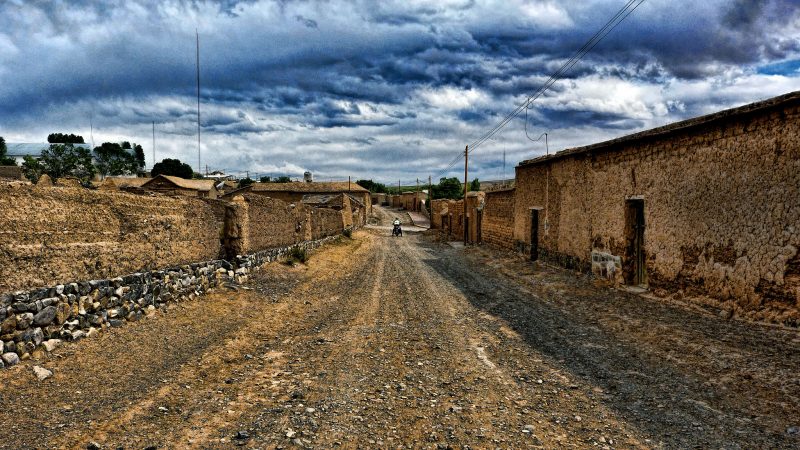

Eleven projects worth $393 million were signed off. But project developers from Paraguay and Argentina seeking $67m between them for sustainable forestry and farming activities in poor areas left empty-handed.

British representative Josceline Wheatley raised a list of technical objections. Notably, he suggested that the proposed level of grant funding – as opposed to loans – was overly generous for middle income countries.

Several of his fellow board members expressed frustration at Wheatley’s stance. Decisions are made by consensus at the UN’s flagship climate finance body, set up with equal representation from developed and developing countries.

One of the unsuccessful bids, from the Unit for Rural Change of Argentina, was responding to a GCF call-out for projects that devolve decision-making to affected communities. It was only the second such “enhanced direct access” proposal to go before the board.

Examples of how the money would be spent included rainwater reservoirs to help smallholders through lengthening dry seasons and solar panels for a community fruit processing plant.

Wheatley said he was “supportive in general” of this approach, but the proposal was “not yet mature”. The cost of $765 for each beneficiary was higher than typical and he was not convinced it would scale.

Report: Climate-hit Bangladesh struggling to access UN green funds

Others argued that the point of the exercise was to pilot novel approaches and learn from them. The GCF’s independent technical advisors recommended approving the project with conditions.

“Part of the idea of the [request for projects] was about understanding and presenting the potential to the world for the GCF to do things differently,” said South African representative Zaheer Fakir. After the failure to reach consensus, he added: “It is rather tragic that this is the kind of message that we are sending.”

It is not the first time the board has been unable to agree. Two projects previously put forward by the UN Development Programme (UNDP) for Bangladesh and Ethiopia were seen as insufficiently climate-focused by developed country members.

Developers are free to resubmit their proposals at a later date. A revised version of the Ethiopian scheme, this time led by the government’s finance department and asking for half the sum of money, was approved at the Cairo meeting.

“We have been here before,” said Tosi Mpanu Mpanu, board member from DR Congo. “We should stop punishing countries and project proponents for our mistakes, for us not having done our homework and finalised some of the policy gaps we have.”

Comment: Climate adaptation cash is failing to reach the poorest – here’s how to fix it

As Climate Home reported from a conference in Dhaka last month, developing country institutions find delays and hefty paperwork demands off-putting.

A core principle of the GCF is to support developing country “ownership” of spending. But it also demands that partners meet international fiduciary standards, which few institutions in poorer countries can be immediately equipped for. That has led to a disparity as the fund started dispersing cash.

A report published by Friends of the Earth and the Institute of Policy Studies ahead of the Cairo meeting found that only 7% of the $2.2 billion so-far allocated was flowing through national or subnational institutions.

The rest is to be disbursed by international institutions, which have more capacity for the upfront paperwork demands. Just three – European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, UNDP and European Investment Bank – are responsible for half the money.

“The Green Climate Fund was supposed to learn from the failures of big development institutions like the World Bank, not channel most of its funds through them,” said Oscar Reyes of Institute for Policy Studies. “There’s plenty of evidence that devolved decision-making is the best way to meet the needs of vulnerable communities at the frontlines of climate change.”

Of the 11 projects approved in Cairo, two were led by national institutions. The board also accredited five funding partners, all from developing countries.

Karen Orenstein from Friends of the Earth said this showed “some improvement” in direct access, but the balance was still “highly in favour” of big multilateral agencies.

The UK’s decision to block the Argentinian project in particular was “regrettable,” she told Climate Home. “This project targets vulnerable rural communities and is not revenue-generating, so of course the project would need grants.”