It could be the climate agreement of the year.

In the coming two weeks 173 states at the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) will discuss what a greenhouse gas reduction plan for shipping first proposed back in 1997 could look like.

The idea is that an initial strategy including a long term target is agreed in 2018, followed by a more comprehensive set of measures and policies due by 2023.

Maritime carbon emissions are estimated to be 2-3% of the global total, but left unchecked that could spiral 250% by mid century, according to a 2014 study by the IMO.

So what do we know about this sector – which carries around 80% of global trade?

Decarbonisation by 2035 is possible

So says the OECD in a report published in March 2018. What’s more, it’s achievable using current technologies, a finding that will surprise anyone used to listening to shipping executives moaning that none of this is possible before someone invents a magic fuel.

But some actions are needed now, says OECD. These include

– A clear, ambitious emissions-reduction target to drive decarbonisation from IMO

– More research into zero carbon tech, more transparency from shipping lines on carbon footprints

– A carbon price for global shipping, leaving it to the market to allocate resources optimally

– Ports could differentiate fees based on environmental criteria

– Governments could also work with banks to incentivise green shipping

There’s a warning buried in the report too. Doing nothing means the sector will be emitting the equivalent to well over 200 coal power plants by 2035.

#Aviation and #shipping have increased rapidly over past years, both globally and in Europe. By 2050, aviation & shipping are anticipated to contribute to almost 40% of global CO2 emissions unless further mitigation actions are taken. More: https://t.co/HlUhxEPKcM #climate ✈️🚢 pic.twitter.com/YBWwJvA3Xu

— EU EnvironmentAgency (@EUEnvironment) February 8, 2018

Decarbonisation has broad support

This week 44 countries announced their support for the Tony De Brum declaration on climate and shipping, which calls for an IMO deal this year to “set a level of ambition for the sector that is compatible with that of the Paris Agreement, including a peak on emissions in the short-term and then reducing them to neutrality towards the second half of this century.”

Signatories include the UK, France, Germany, Sweden, Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Mexico, Peru and the Marshall Islands. Opinions differ on the scale of ambition. The Marshalls want complete decarbonisation by 2035, EU member states are suggesting 70–100% by 2050.

Strong words from UK #shipping minister @Nus_Ghani: sector must target GHG deal "in line with the Paris Agreement" – which means net zero in second half of century https://t.co/P33bUcgCgs

— Ed King (@edking_I) March 26, 2018

Current efforts are not cutting it

The IMO’s current plan is a deal to ensure new ships are 30% more efficient by 2025, but this does little in bending shipping’s GHG curve towards keeping global warming well below 2C. A recent study for the Danish Shipowners Association estimated that the likely impact of this policy is only a 3% reduction in the sector’s total emissions between now and 2050.

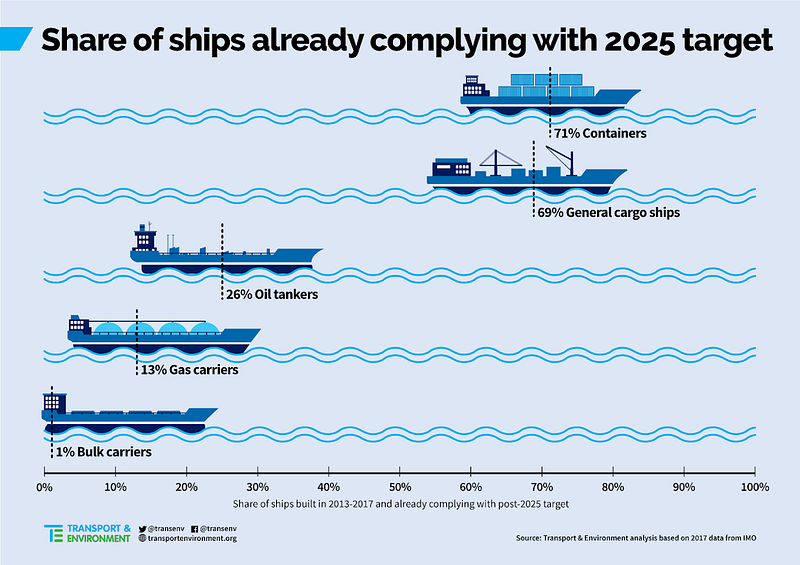

And while the 30% figure sounds impressive, it’s lagging well behind the industry’s current performance. At least 60% of container ships, 50% of general cargo ships and 25% of tankers already meet IMO efficiency targets for 2020, as the graphic below from Brussels-based NGO Transport & Environment illustrates.

Shipping pollution is a killer

That’s according to a 2018 study published in the journal Nature.

“Cleaner marine fuels will reduce ship-related premature mortality and morbidity by 34 and 54%, respectively, representing a ~ 2.6% global reduction in PM2.5 cardiovascular and lung cancer deaths and a ~3.6% global reduction in childhood asthma. Despite these reductions, low-sulphur marine fuels will still account for ~250k deaths and ~6.4 M childhood asthma cases annually, and more stringent standards beyond 2020 may provide additional health benefits.”

Big business wields great power

So said analysts at Influence Map, a group that charts corporate lobbying, in a study published last October.

“Despite being responsible for close to 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions, the shipping sector remains outside of the UN Paris Agreement on climate. It has achieved this through corporate capture of the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the UN body responsible for regulating global shipping.”

The report highlighted the large number of advisers from commodities shipper Vale on Brazil’s delegation. Exxon-Mobil, Saudi Aramco and MSC are other major businesses with significant shipping interests that send officials to take part in IMO talks, frequently as part of national delegations.

Influence Map’s finding prompted an extraordinary response from a senior executive at a major shipping line, who wrote on the online platform Splash 247: “We can feel nothing but contempt and disgust at the prostitutes employed by our racket to try and put one over on the general public.”

For more on the corporate capture of the UN, read this expose on the role of shipping registries — and in particular the US organisation that took control of a Pacific Island’s seat at the UN.

Technology is starting to shift the dial

Change is slow, but it is happening. IKEA and Maersk are among the larger companies to acknowledge climate risk and set targets to clean their business / supply chains. Others such as Hurtigruten — a cruise firm — are working on hybrid ships, while Siemens is pioneering deployment of electric ferries.

According to the OECD, further efficiency improvements are still possible on existing hulls and propellers. Wind (yes — wind!) assistance has huge potential for a large number of ships in the fleet, to tap this free energy source.

Still, while energy demands per ship will therefore be lower, deep sea shipping will still need a renewable fuel given the potential of batteries over long distances are not yet proven.

– Shell [see their 2017 hydrogen case study here], ITM power and Engie are already working on developing hydrogen electrolysers and green hydrogen supply chains.

– Major operators such as Stena and CMB are already pilot these potential fuels and class societies are developing rules — Lloyds Register recently classed the first deep sea hydrogen ship.

– Fuel cells may be the ultimate solution for shipping, and are developing fast in both performance terms and reduced costs as “marine scale” units of many MW’s are developed. They also offer much lower maintenance costs and like batteries pave the way to autonomous deep sea shipping.

Keep an eye on Port Liner, who are building a fleet of 100% electric barges to run between Antwerp, Amsterdam, and Rotterdam — as covered in a recent DW report.

“It simply doesn’t make sense for us to build new ships with diesel engines,” Ton van Meegen, chief executive of Port Liner, a €100 million ($124 million) EU-supported venture, told DW. “Our vessels will be used for decades, and electric motors are clearly where the industry is headed.”

It’s hard for journalists to operate at IMO

Don’t get me wrong – the food is nice and we are given water. The press team are friendly people. We’re not shot at or threatened. But the IMO does have weird rules governing how reporters can operate.

So if – for instance – a small island state happens to say climate change is over-rated and there’s no point in discussing the issue – you’re not allowed to report this, unless you get the express permission of the person who said it. Who, in most cases, will say no.

Reporters are allowed to write about outcomes, but not process. In IMO parlance “this specifically precludes reporting of the discussions themselves” which for anyone who has worked at other UN venues is – quite simply – rather unique. And rather defeats the purpose of having media watching proceedings.

It’ll be harder and expensive for ports to operate in a warming planet

That’s the finding of an HSBC study into the risks Asia’s top ports face from climate change.

“Upgrading Asia-Pacific’s biggest ports to cope with the effects of climate change will cost up to $49 billion, but the bill could be even higher if no action is taken,” Reuters reported.

“ARE’s report — commissioned by international bank HSBC — covered ports in Japan, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia, India, South Korea and Malaysia. It put the costs for those ports to adapt to climate change at between $31 billion and $49 billion.

“Japan’s Kitakyushu port faces the highest cost at $4.9 billion, the report said, while five of the region’s 10 largest ports by capacity could see bills of more than $1 billion each.”

Shipping is key to limiting warming to 1.5C

In 2015 countries agreed to try and limit warming to well below 2C and aim for 1.5C – so far progress has been limited – but what’s clear is that all sectors need to deliver. The 1.5C goal is important for small island states and other low lying countries, as Carbon Brief explains here:

“An extra 0.5C could see global sea levels rise 10cm more by 2100, water shortages in the Mediterranean double and tropical heatwaves last up to a month longer. The difference between 2C and 1.5C is also “likely to be decisive for the future of coral reefs”, with virtually all coral reefs at high risk of bleaching with 2C warming.”

Yet as this chart illustrates, not everyone is on board — least of all Japan and the International Chamber of Shipping. The key over the next two weeks will be — as ever — not what member states and lobby groups say in terms of framing “ambition”, but what they’re prepared to put on the table.

#3 – why claims by @shippingics that it backs ambitious #climate plans are a #loadofoldballs pic.twitter.com/swASNc8d3k

— IMOclimate (@IMOclimate) January 10, 2018

This article was originally published on Medium. Ed King is a consultant working on shipping decarbonisation supported by the European Climate Foundation. He is the former editor of Climate Home News.