China reaffirmed its commitment to its climate goals at last week’s party congress and is likely to over-achieve its renewable targets in Xi Jinping’s third term in power, experts told Climate Home News.

But an undecided growth model, emphasis on energy security and rising geopolitical tensions are expected to pose challenges to its decarbonisation process, they said.

While some experts hoped that China would peak its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the next five years, others considered the nation’s overall emissions trajectory “more uncertain” due to the unpredictability of its growth model.

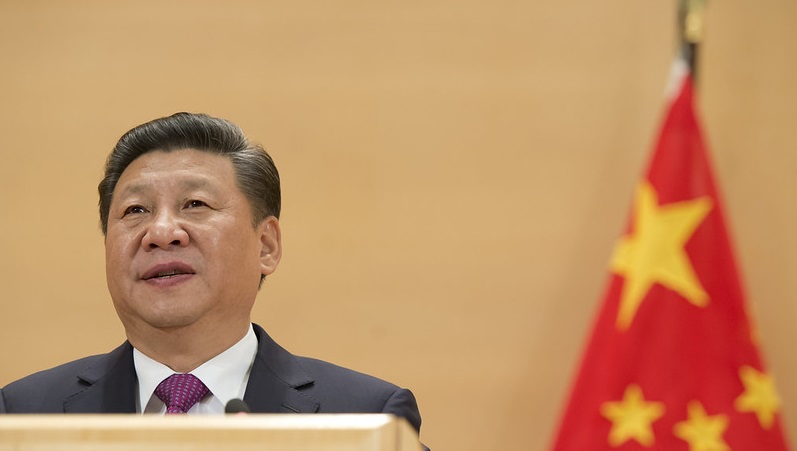

Xi cements control

On Sunday, Xi became the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party – the highest position in the country’s ruling political party – for the third consecutive time. He will lead the party until 2027.

Over the past two years, climate action has played an important role in Xi’s leadership.

In September 2020, he pledged that China would peak its carbon dioxide emissions “before 2030” and achieve carbon neutrality “before 2060”. He is believed to have personally promoted these two targets, which are known as the “dual carbon” goals.

At the congress last week, he reiterated these goals in a lengthy speech setting out the party’s priorities for the next five years. The goals also appeared in an accompanying 25-page report.

Kevin Mo is the principal of Beijing-based green consultancy iGDP. He said that, while none of the instructions were new, their incorporation into the report brought a new level of significance to China’s climate agenda and was “a very important” step in the nation’s political system.

Emissions peak

Wu Changhua, regional director at the office of green activist Jeremy Rifkin, told Climate Home that she would be watching China’s emissions-peaking timeline.

“Although China has said it would peak its emissions ‘before 2030’, it has never clarified how much ‘before’ the peaking would be or at what level the emissions would top out,” said Wu.

In March, a study from the Chinese Academy of Engineering (CAE) projected that China would peak its CO2 emissions “around 2027” at “about 12.2 gigatonnes”. The IEA estimates that emissions were 11.9 gigatonnes in 2021. However, it remains unclear if CAE’s projection had considered the impact of China’s recent focus on energy security.

Wu said this peaking timeline is “hopeful” but she warned that, since Xi made its “dual-carbon” goals in 2020, China’s “internal and external conditions” – such as its domestic economy and international relations – have both changed “dramatically”, leading to challenges for its climate pledges.

She will also look at how China pushes its clean energy transition, develops a “new energy system” and expands the national carbon market. All of these were mentioned in Xi’s latest speech.

On clean energy, Wu said that China has “made the case” of exceeding its announced targets “in many ways”, such as scaling renewable energy and putting electric vehicles on the road.

For example, projections have shown that the combined installation capacity of China’s wind and solar would exceed 1,100GW by 2025 if their expansion sticks to the current pace. The figure is far ahead of China’s current announced target of “over” 1,200GW by 2030.

“How much more the country would be able to beat the targets for 2025 and 2030 would be some of the major milestones under Xi’s leadership,” she said.

Clean or dirty growth?

But E3G advisor Byford Tsang said China’s emissions trajectory for the next five years is “more uncertain”. He said emissions could “go up or down” depending on the country’s economic strategy.

On Monday, the Chinese government reported 3.9% year-on-year economic growth in the third quarter of this year, which outstripped the forecast of 3.2-3.3%. However, economists warn that longer-term growth will be challenged by Covid-19 curbs, a prolonged property slump and the risk of a global recession.

“If China decides to boost the economy the traditional way, with investments that stimulate infrastructure sectors, it would mean that emissions could go up,” Tsang said. “But if we see more radical policies that could lead to an economic slowdown, like [what happened to] the real estate sector, for example, then we may see emissions going down.”

Edmund Downie, a Princeton international affairs PhD student, said: “A lot of the hopes and challenges for China’s climate transition over the next five years are, in many ways, tied up with the hopes and challenges for China’s economy over the next five years.”

He said “there are real hopes” for the country to peak its CO2 emissions before the end of Xi’s third term in 2027. But “the hard question” is whether China could transition its economy past its reliance on real estate, which supports high-emitting sectors like cement and steel, to a low-carbon model.

Emphasis on energy security

China’s energy security policy adds to the uncertainties for its climate agenda under Xi’s third term, experts said. As China has abundant supplies of coal, energy security is often tied up with the fuel.

Mo said: “It is still to be observed if coal would be used as a short-term measure to ensure energy security or a long-term, basic source of energy.”

He said it is unlikely that coal would be “abandoned completely” in the short term and, even in the long run, weaning the country off the fuel would be difficult.

“Therefore, the ‘clean’ use of coal, with technologies such as carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), has been highlighted,” Mo said. He expects coal to continue to be China’s main source of energy in the next five years, based on his understanding of Xi’s latest speech.

Besides China’s domestic economy and fossil fuel policy, international geopolitics will likely bring more hurdles for its climate agenda. Technology sharing, global supply chains and cross-border trade will be particularly difficult.

Geopolitical breakdown

The US-China geopolitical contention “continues to escalate”, said Wu. She added: “Each has become the biggest security threat to the other. Each has adopted a national strategic shift to enhance its own resilience.”

Mo expects geopolitics to pose “quite a big challenge” to China’s fight against climate change in the coming years. He said other countries used to view climate change as an area in which they could cooperate with China, “but right now, in fact, competition has emerged in climate change… and it is expected to get more fierce”.

On the bright side, E3G climate diplomacy researcher Belinda Schäpe said adapting to climate change has “really gained importance” in China. She said the government’s new adaptation strategy is “much more ambitious” than the previous version.

She expects these improvements to continue, especially after China experienced the “longest and strongest heat wave on record” this summer.