The history of the annual UN climate talks, now in their 27th year, is marked by setbacks, delays and inaction from the world’s rich carbon emitters – all while the climate crisis continues to devastate countries and communities in front of our very eyes.

So, it is a joy to see this year’s meeting, which happened to take place on African soil in Egypt’s Sharm El-Sheikh, finally respond to the calls of those on the front line of the climate emergency.

Countries at Cop27 agreed to create a special fund for “loss and damage” which will effectively compensate people who have suffered the most severe climate impacts, ones so bad they cannot be adapted to.

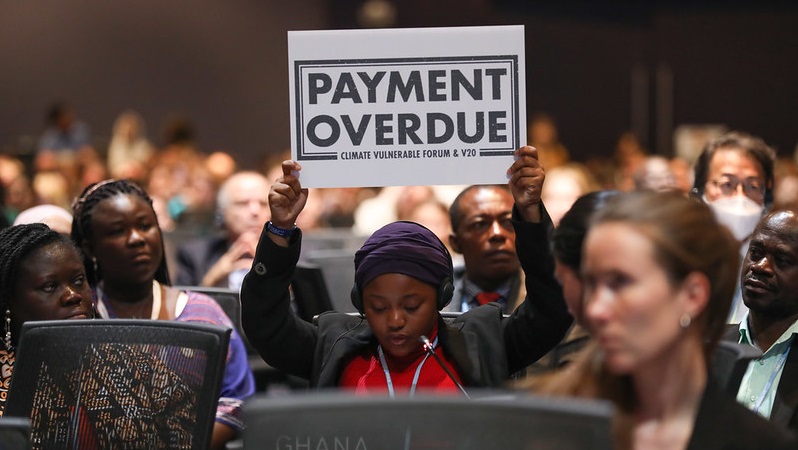

It’s a remarkable achievement considering that vulnerable countries had to fight to even get the issue on the agenda in the first few days of the meeting. Many of us weren’t convinced we would get this positive outcome halfway through the two-week summit in Sharm.

But in the negotiating rooms and conference halls, the developing countries, with civil society support, fought as if their lives depended on it because they do. The cause of climate justice prevailed. How is it fair that those suffering loss and damage caused by others, not themselves, should have to pay for it?

Creating the fund is one thing, but it’s currently an empty vessel. The next task is to get money flowing through it to the frontline communities that need it.

Root causes

Although the meeting made a major step in dealing with the consequences of climate change, it made less progress tackling the root causes of the problem.

We had hoped to build on the agreement secured in Glasgow last year at Cop26, that saw countries agree to a global phase down of coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel.

A number of countries sought to secure a commitment to phase down all fossil fuels, including oil and gas, but those efforts were thwarted by Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iran among others.

It’s infuriating to see the science become clearer, the climate impacts become more devastating, and the cost of fossil fuels worsen, and yet countries refuse to do the one thing we all know needs to be done to stop the world from destroying itself. 90% of all coal reserves and 60% of oil and gas reserves must be left in the ground if we’re going to secure a planet which is prosperous and safe to live on.

Analysis: What was decided at Cop27 climate talks in Sharm el-Sheikh?

However, the forces of progress and climate common sense fought hard in Sharm El-Sheikh for a fossil fuel phase down to be secured, so much so the momentum will now build ahead of next year’s meeting in the United Arab Emirates. And we take heart from the victory of the vulnerables on loss and damage.

Twelve months ago, we left Glasgow disappointed that no loss and damage fund had been created. But we knew the case was so strong, and the voices so loud, that rich nations would not be able to ignore us again. And so it proved last week.

The end of oil and gas

We now need to spend the next twelve months ensuring the end of the oil and gas era is heralded in 2023. And what better place for it to happen than in an Opec country?

Already, there are signs that the reign of the fossil fuel industry is beginning to crack. For the first time a Cop decision document included language around the expansion of renewables.

World leaders who attended the summit, such as Kenya’s president William Ruto, championed the benefits of clean power and outlined why they were leaving their fossil fuel reserves in the ground.

Witnessing African leadership on African soil was a proud moment for this African. There’s no reason we can’t see our entire continent becoming pioneers for such forward-thinking energy policy. After all, Africa contains 39% of the world’s renewable energy potential.

Another sign the fossil fuel industry is getting nervous is just how many lobbyists they are now sending to these annual climate talks to try and disrupt them in favour of flogging their product of pollution.

This year saw a record number of fossil fuel industry delegates, more than 600. A few years ago, they wouldn’t have bothered but they know the growing demand for action on climate change by the public and that the transformative potential of clean energy is a threat to their century-long monopoly of the global energy market. So much so they have distorted the world’s carefully balanced climate during that time.

We still have a long way to go, and the indifference of the fossil fuel companies at the climate suffering they cause knows no bounds. But the victory of the vulnerables in Sharm shows what can be achieved when enough people get behind a good idea and gives us confidence that we can, and must, end the world’s addiction to fossil fuels.

Mohamed Adow is the director of Power Shift Africa.