World leaders were asked to come to the UN with concrete plans to cut emissions to net zero.

But on Monday, the presidents and prime ministers of the world’s largest emitting economies stumbled. Signalling just how difficult the work of removing CO2 will be compared to setting targets.

The tougher 1.5C goal of the Paris Agreement, backed by UN chief António Guterres and the majority of the world’s nations, requires achieving net zero global emissions by 2050.

Guterres asked leaders to come to UN headquarters in New York and tell the world how they would meet that goal.

A coalition of 77 smaller countries said they were committed to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and 70 countries expressed their intention to set a more ambitious climate plan next year, evidence of “a boost of momentum and ambition,” Guterres said in his closing remarks.

While there were “inspiring signs of progress”, with “the private sector and subnational actors moving faster than national governments”, “most of the major economies fell woefully short” of enhancing their ambition, said Andrew Steer, president and CEO of the World Resources Institute.

“Much more it still needed to reach carbon neutrality by 2050,” Guterres warned.

The “how” of the question, which requires countries to integrate climate action into economy-wide policies, was left unanswered. Fully decarbonising the world economy is a gargantuan task, even for the world’s richest countries.

The path to net zero emissions “is something we are just discovering,” former French climate ambassador and CEO of the European Climate Foundation Laurence Tubiana told CHN. But the top levels of government are not yet engaged.

“I haven’t met any leaders who know… how to get there. Most [countries] haven’t started really seriously” and most leaders “don’t have a clue” how they will meet a 1.5C compatible target.

According to Elina Bardram, head of unit for climate action at the EU Commission, while “numbers and slogans are very easy to go by but the hard work of actually implementing is what drives the process forward”.

Both the UK and France, which have already legislated to become carbon neutral by 2050, have been warned by their climate advisors that without new and robust carbon-cutting measures, they won’t be on track to meet the 2050 goal.

“That’s what we are going to do”, said UK prime minster Boris Johnson said on Friday, by using “technology”.

Michal Kurtyka, Polish environment minister and president of Cop24, told CHN that achieving carbon neutrality was “a civilisational challenge”. Poland was one of four countries that blocked an EU agreement for the block to achieve net zero emission by 2050 in June – leading the EU to turn up to the summit with only hints at promises.

Net zero: the story of the target that will shape our future

Germany’s environment minister Svenja Schulze, acknowledged her government does “not know exactly how to reach carbon neutrality”, a goal set by chancellor Angela Merkel at the summit.

“We know how to get to 2030 but the last percentage to reach carbon neutrality, we need more techniques, we need new ideas,” Schulze told CHN, adding that “no-one around the world does [know] exactly”.

“The important thing is to say that we want to reach that goal. How is goes with the last percentage, we will see on the way,” she added.

China conversely appears to be wary of setting goals that it does not know it can achieve. Its climate targets are barely better than “business-as-usual”, said Tubiana.

But the window for action is narrowing. Global emissions continue to rise year-on year – increasing the gap between the 1.5C goal and current pathways to get there and closing the door to incremental emission reductions.

“We are still operating a logic of ‘let’s reduce emissions’, even if it’s very small, it’s helpful,” director general for DG Clima at the European Commission Raffaele Mauro Petriccione told CHN. “But we are now moving towards a radical different logic which is we need to eliminate most emissions and then the choices are most difficult.

“We are, in half a century trying to reverse 150 years of very fast economic development based on fossil fuels. It’s possible and it’s desirable, but one shouldn’t be surprised that it’s complicated.”

This is a reminder that CHN is small independent news site, dedicated to bringing you news from all over the world. That’s expensive and we need our readers to help. Here’s how you can, even for a few dollars a month.

And yet, incrementalism was the main theme at the UN climate action summit, as heads of state took to the podium one after the other.

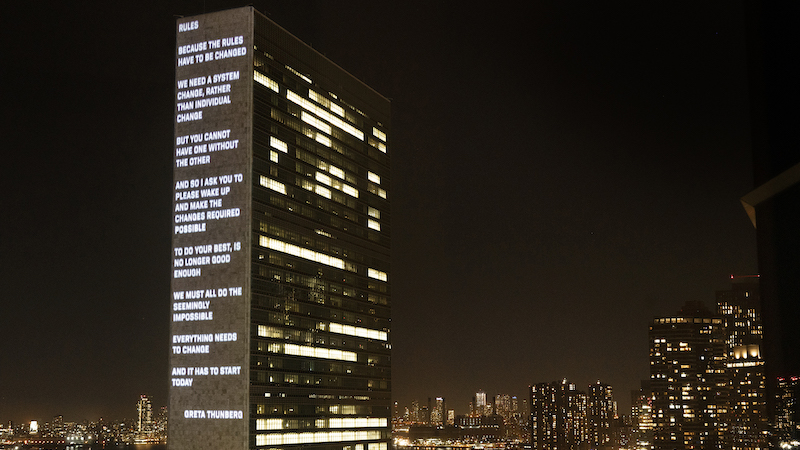

The speeches failed to resonate, except for Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, who brought the hall to tears as she called out leaders for their inaction.

“Yet you all come to me for hope? How dare you,” she said.

From China and India there was “nothing”, Tubiana told CHN.

The absence of Chinese president Xi Jinping’s, as the leader of the world’s largest emitting country poured cold water on any expectations of a significant announcement. Instead, Wang Yi, a special representative of Xi, said China would meet its Paris pledge but made no suggestion of when and how Beijing would hike its climate plan and peak its emissions, let alone start the process of reducing them.

Indian prime minister Narendra Modi made no mention of reducing its coal dependence; one of Guterres’ key demands. Instead, Modi said India was planning to turbocharge the roll out of renewable energy to 450GW.

‘We will not forgive you’: Greta Thunberg’s speech to leaders at UN – video

The lack of announcements on coal showed the “extremely difficult political shifts” this represents for India, where 75% of the country’s electricity is generated by coal, said Rachel Kyte, the UN secretary general’s special representative for sustainable energy.

“You are going down in the economy and trying to strip one of the fundamental pieces of sub-structure,” she said.

EU Council president Donald Tusk said was only a matter of time for the bloc to adopt net zero emissions by 2050 as its target – but gave few details of how the world’s largest economic bloc was going to transfer away from fossil fuels.

This comes down to leadership. Economy-wide shifts cannot happen “unless it comes from the strong will of the head of state” which can bypass individual ministries, said Isabel Cavelier, a former Colombian climate negotiator and a senior advisor to Mission2020.

There are examples of change. Denmark’s new government which was elected with an ambitious climate target to reduce emissions by 70% by 2030 – something Dan Jorgensen, a Danish social democrat member of parliament and former minister, acknowledged was “a daunting task”.

The new Danish government is changing the structure of decision-making, by appointing a committee on climate change to which all other ministries will be accountable.

“What you are starting to see is governments reorganising themselves,” Kyte said.