Scientists are monitoring the atmosphere at a mountaintop in Hawaii for clues that the coronavirus will be the first economic shock in more than 60 years to slow a rise in carbon dioxide levels that are heating the planet.

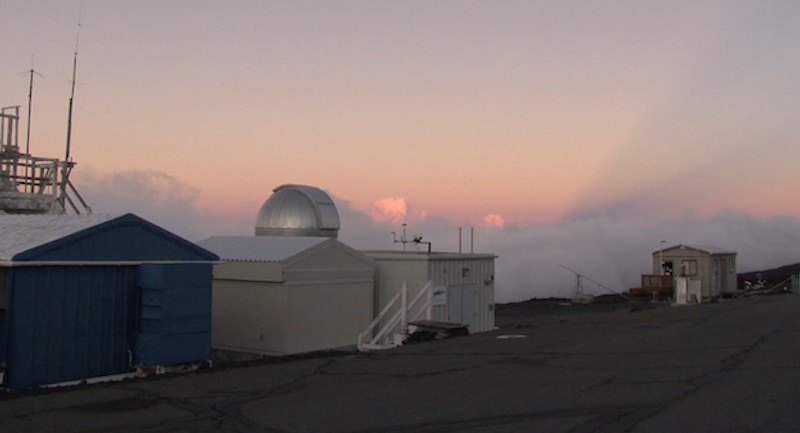

The Mauna Loa observatory at 3,397 metres is home to the Keeling Curve, tracking increasing carbon dioxide concentrations since 1958. Named after its late founder, Charles Keeling, it is widely viewed as the most iconic measure of humanity’s impact on global climate.

“There has never been an economic shock like this in the whole history of the curve,” Ralph Keeling, professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego and son of Charles Keeling, told Climate Home News of the impact of the coronavirus.

He said scientists were now studying data from the mountain in the middle of the Pacific Ocean for signs that the economic slowdown linked to the coronavirus could reduce the rise in atmospheric carbon concentrations.

The coronavirus, which has killed more than 22,000 people by 26 March, is slowing the global economy and cutting the use of fossil fuels in cars, power plants and factories that emit carbon dioxide. “I can look out of my window now and the number of cars has dropped,” he said.

Russia’s plans to tighten 2030 climate goal criticised as ‘baby steps’

But there was a long way from reduced use of fossil fuels to a crisis that would affect carbon dioxide concentrations in the global atmosphere.

Keeling estimated that global fossil fuel use would have to decline by 10% for a full year to show up in carbon dioxide concentrations. Even then, it would be a difference of only about 0.5 parts per million.

Since 1958 there have been no world wars, for instance, that might abruptly depress economic activity and emissions and show up as a measurable impact on the curve, he said.

Recessions, like the 2008-09 financial crisis or even the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, did not cause a discernible drop. And other factors that have tended to drive the curve up more steeply, such as the economic rise of China this century, were not visible as sudden events.

This March 2020 data may hint at a slight slowdown in the rate of rise.

“It’s too early to say,” if it is related to coronavirus, Keeling said, adding there were big variations from year to year and that the March trend was similar to some previous years.

Two-year record of carbon dioxide (Source: Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Current carbon concentrations “are approaching last year’s peak right now,” he said, at about 415 parts per million on 24 March, with big daily swings. If sustained, that is already in line with the record high, judged as a monthly average, of 414.7 ppm for the May 2019.

Carbon dioxide levels have risen from about 270 ppm before the Industrial Revolution and are at the highest in at least 800,000 years, according to the UN panel of climate scientists.

Governments urged to attach green strings to long-term coronavirus recovery plans

Carbon dioxide concentrations have their annual peak at the end of winter in the Northern Hemisphere, where North America, Asia and Europe make up most of the planet’s land masses. When spring arrives, plant growth on these continents soaks up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, slightly reducing levels.

Keeling likened economic activity affecting the atmosphere to a tap pouring water into a bathtub.

If you turn down the tap in a bathtub you can see there is less water coming in “but it takes a while to be able to see that the rising water level slows,” he said. “We’re still in that phase.”

The Keeling Curve, Mauna Loa Observatory

On the other side of the world in Norway, Kim Holmen, international director of the Norwegian Polar Institute, says his team is also closely monitoring carbon dioxide levels at the Zeppelin station on a mountain on the Arctic island of Svalbard.

“The curve is not pointing upwards,” he said of carbon dioxide measurements in March, which are usually rising at this time of year. Still, he said that it would probably take months to know if it was related to coronavirus.

Climate news in your inbox? Sign up here

And he said there were many local factors affecting carbon levels, even in parts of the world isolated from industrial centres such as Hawaii or Svalbard.

Around Svalbard, for instance, “it has been colder this winter than the past 10 years,” Holmen said. That meant there had been more ice on the surrounding seas in the winter, putting a lid on waters that can release carbon dioxide into the air.

The UN wants steep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions to limit rising temperatures to goals set in the Paris Agreement of “well below 2C” above pre-industrial times while pursuing efforts for a stricter ceiling of 1.5C.

Emissions rose sharply after the financial crisis but Keeling expressed hopes that policy makers would help drive cuts in coming years, after the pandemic passes.

“We can hope that emissions stay down for the right reasons afterwards. This [coronavirus] is not the right reason,” he said.