Joe Biden has promised to double US international climate finance by 2024 and triple funding for adaptation, in a bid to restore US credibility on tackling the climate crisis.

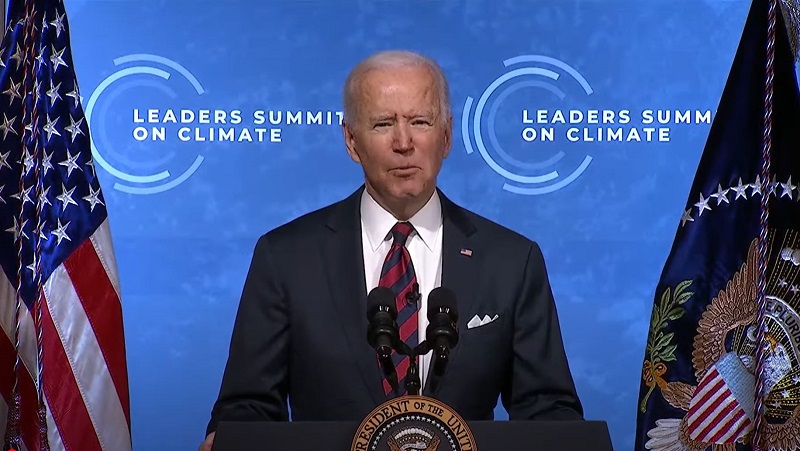

“Good ideas and good intentions aren’t good enough, we need to ensure that financing will be there to meet the moment on climate change,” the US president said at leaders’ climate summit he convened on Earth Day.

The increase in finance is set against the average climate finance delivered during Barack Obama’s second term, 2013-16. While no dollar figure is given in the plan, administration official Leonardo Martinez-Diaz told Climate Home News the baseline was around $2.8 billion, with $500 million of that going on adaptation. Adding in contributions to multilateral development banks and mobilised private finance, the total could reach around $15 billion a year, he said.

Joe Thwaites, of the World resources Institute, said the climate finance plan was “not particularly ambitious” after four years of US absence, during which time many other major donor countries doubled their climate finance pledges.

“The US has made an important start, but must do much more if it wants to become a leader on climate finance. Provision of finance to vulnerable countries is a central pillar of the Paris Agreement, and such investments are key to building credibility and influence to unlock more ambitious climate action from other countries, delivering benefits at home and abroad,” he said.

Brandon Wu, director of policy and campaigns at ActionAid USA, described the numbers as “very low” and far cry from the $800 billion this decade campaigners say would be a fair contribution from the US.

The finance package made no mention of replenishing the Green Climate Fund, the UN’s flagship climate finance initiative, which has been hit by whistleblower complaints of a “toxic” workplace and political interference. However, it affirmed a commitment to end public finance investment in support for “carbon-intensive fossil-fuel based energy projects”.

As it happened: US, Japan, Canada pledged deeper emissions cuts at Biden summit

At home, Biden pledged to cut emissions 50-52% by 2030, compared with 2005, in a heavily trailed target to restore US action after four lost years under Donald Trump.

“The signs are unmistakable. The science is undeniable but the cost of inaction keeps mounting and the United States isn’t waiting,” Biden said, urging countries to get on a path consistent with halting global heating to 1.5C.

The US’ 2030 climate goal is a significant step up in ambition and will close the global emissions gap by 5-10% by 2030, according to Climate Action Tracker.

However, it fails to put the US on track to meeting the 1.5C goal which would require emissions cuts of 57-70%, analysts say.

Biden had asked 40 world leaders from some of the largest emitting and most vulnerable nations to set out immediate climate action to curb emissions in the next 10 years.

While there were some new pledges, the summit failed to go beyond incremental increases in ambition by major emitters.

Hopes for a “50% club” of nations committing to halve their emissions fell flat. Japan pledged to reduce emissions 46% by 2030 compared with 2013 levels and did not announce an end to overseas coal financing, as some expected.

Prime minister Justin Trudeau said Canada would cut emissions 40-45% between 2005 and 2030 – a far cry from campaigners’ call for a 60% emissions cuts.

South Korean president Moon Jae-in said he would announce an improved 2030 goal later this year, meanwhile promising to end the country’s significant investment in coal power internationally.

Very disappointed in Canada’s weak target of only 40-45%. They should do better as the 10th largest emitting country in the world!

— Jake Schmidt – NRDC (@jschmidtnrdc) April 22, 2021

President Xi Jinping said China would peak its coal consumption by 2025 and gradually reduce its coal reliance during the country’s next five-year economic planning cycle.

“Action on coal has never been explicitly linked to China’s climate ambition. Now President Xi is saying, ‘hey coal, this means you too!’,” said David Vance Wagner, vice president of Energy Foundation China and a former US official who led US-China dialogue on climate change under Barack Obama.

But Xi did not announce any increase in the ambition of China’s targets to peak emissions in 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2060.

His statement left room for increasing coal consumption over the next five years, said Byford Tsang, who leads think tank E3G’s China work, and brings little clarity to the policies Beijing will put in place to meet its emissions goals.

China is projected to account for more than 50% of global growth in coal demand this year, according to the International Energy Agency. This has been driven by a coal-fired Covid recovery across some of the country’s provinces.

Stay in the know: Subscribe to our daily or weekly newsletter

Analyst say that to align policy with its long-term carbon neutrality goal, China needs to immediately stop building new coal-fired power plants and shut 364 gigawatts of coal capacity by 2030 – down from an estimated 1,095GW currently.

Li Shuo, senior climate and energy officer at Greenpeace East Asia, told Climate Home News “more ambitious actions” were needed from Beijing.

“The domestic conditions for faster emission reduction is becoming mature. It is in China’s self-interest to announce and implement further plans ahead of Cop26,” he said.

South Korea’s commitment to end overseas financing for coal-fired power plants will put pressure on Beijing and Tokyo to follow suit.

Between 2016 and 2018, China was the largest provider of public finance for fossil fuels overseas, while Japan spent an estimated $4.2bn a year on supporting coal projects abroad.

Large developing nations including Indonesia, South Africa and Bangladesh said richer nations needed to commit more climate finance for them to accelerate emissions cuts.

Bangladesh’s prime minister Sheikh Hasina said the country was already spending about $5 billion, or 2.5% of its GDP, every year on coping with the impacts of the climate crisis.

“Developing countries often suffer the most devastating impact of climate change. Consequently, developed economies have a responsibility to support developing economies, to support them to mitigate and adapt to climate change,” said South African president Cyril Ramaphosa.