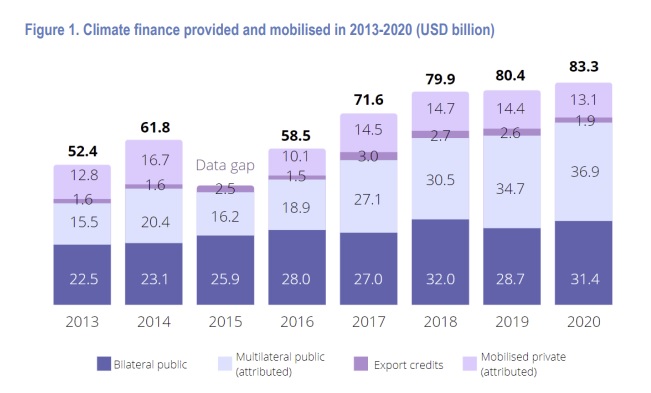

Rich countries have fallen almost $17bn short of their pledge to collectively deliver $100 billion of climate finance a year by 2020, according to the latest data by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The data shows that in 2020, rich nations mobilised $83.3 billion of climate finance, a 4% increase on the previous year but short of the $100bn target that they set themselves in 2009.

2020 was the deadline for achieving the $100bn climate finance goal. Developed countries are now only expected to meet it in 2023. Previous research suggests that the US is responsible for the vast majority of the shortfall.

The bulk of the funding was in the form of loans rather than grants and went to Asian and middle income countries.

Asia received 42% of the finance, roughly equal to its share of the global population, while Africa got 26% and the Americas received 17%.

Climate finance to developing countries was spread over five continents (Photo: Wikicommons)

Lower middle income countries received 43% of the funding while upper middle income countries got 27%. Low income countries, which represent about 9% of the global population and are most in need of finance, received 8%.

OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann said achieving the goal next year is “critical to building trust as we continue to deepen our multilateral response to climate change.” Increasing finance for countries worst hit by climate impacts is one of the key goals of Cop27 in Egypt.

“We know that more needs to be done. Climate finance grew between 2019 and 2020, but as we had expected, remained short of the increase needed to reach the $100 billion goal by 2020,” Cormann said. “While countries continue to grapple with the economic and social implications of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, we are seeing climate change causing widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people.”

Joe Thwaites, an international climate finance advocate at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), told Climate Home News that the report “confirms what was largely feared about climate finance in 2020: that developed countries failed to meet the $100 billion goal due that year; that mobilisation of private finance has totally stagnated; and that despite a growing debt crisis most public climate finance remains in the form of loans.”

Climate finance failed to reach $100bn in 2020 (Photo: OECD)

Developing countries have long called for a greater share of finance to go towards adapting to climate change rather than reducing emissions. Mitigation finance, for reducing emissions, dropped by $2.8bn between 2019-2020, while adaptation finance rose 41% by $8.3bn.

Mitigation still receives a larger share of the total (58%) than adaptation. Adaptation funds have gone towards water and sanitation projects as well as forestry, agriculture and fishing, the OECD report notes.

“It is good to see that adaptation finance grew significantly in 2020, making the COP26 commitment to double adaptation finance by 2025 look achievable, on route to reaching the balance with mitigation finance that the Paris Agreement calls for,” Thwaites said.

The OECD update was published earlier in the year than usual to fit UNFCCC timelines.