Temperatures in parts of Chile and northern Argentina have soared to 10°C-20°C above average over the last few weeks. Towns in the Andes mountains have reached 38°C or more, while Argentina’s capital, Buenos Aires, saw temperatures above 30°C – breaking its previous August record by more than 5°C. Temperatures peaked at 39°C in the town of Rivadavia.

Bear in mind it’s mid-winter in this part of the world. And it’s far south enough that seasonal variations have a substantial impact on temperatures. Buenos Aires, for instance, is as far south as Japan, Tibet or Tennessee are north.

In terms of deviation from temperatures you might expect at a certain place and time of year, this heatwave is comparable to, if not greater than, the recent heatwaves in southern Europe, the US and China.

In Vicuña, one of the towns in the Chilean Andes that recently reached 38°C, a typical August day might be 18°C or so – just imagine it being a whole 20°C warmer than normal wherever you are now.

No wonder some climate scientists have already suggested this could be one of the most extreme heatwaves on record.

What’s causing the extreme heat?

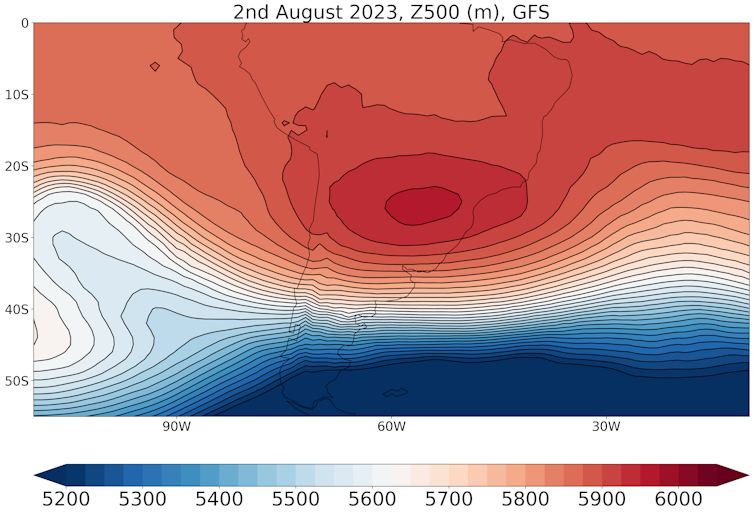

Over the past six days, a persistent area of high pressure, or anticyclone, has lingered to the east of the Andes. Also known as a “blocking high”, this appears to be the key driver of the intense heat.

GFS analysis data, Author provided

Blocking anticyclones can drive heatwaves in three main ways. Firstly, they pull warmer air from closer to the equator towards them. The system also compresses and traps the air, heating it up, as was the case for the 2021 heatwave in the Pacific Northwest, which shattered the Canadian temperature record by nearly 5°C. Finally, the high pressure means there is little ascending air and hence little cloud cover. This allows the sun to heat the land continuously during the day, building up heat.

However, scientists need to analyse the meteorology of this unprecedented event in more detail to gain a more complete understanding.

El Niño made this more likely

The Chile-Argentina heatwave may have been made more likely by the developing El Niño in the Pacific Ocean. El Niño events, which typically occur every four years or so, are characterised by warm sea surface temperatures in the central-to-eastern tropical Pacific. Temperatures in the central Pacific are currently about 1°C above average for the time of year.

These warmer ocean temperatures make air more buoyant over the central Pacific, causing the air to rise. This drives changes to atmospheric circulation patterns further afield. El Niño-induced changes to atmospheric circulation typically mean higher pressure and warmer winter temperatures for this part of South America.

Climate change made it worse

The blocking system driving the extreme heat would probably have led to warm temperatures even in the absence of anthropogenic climate change. However, the rapid warming of climate change allowed the heatwave to become truly unprecedented.

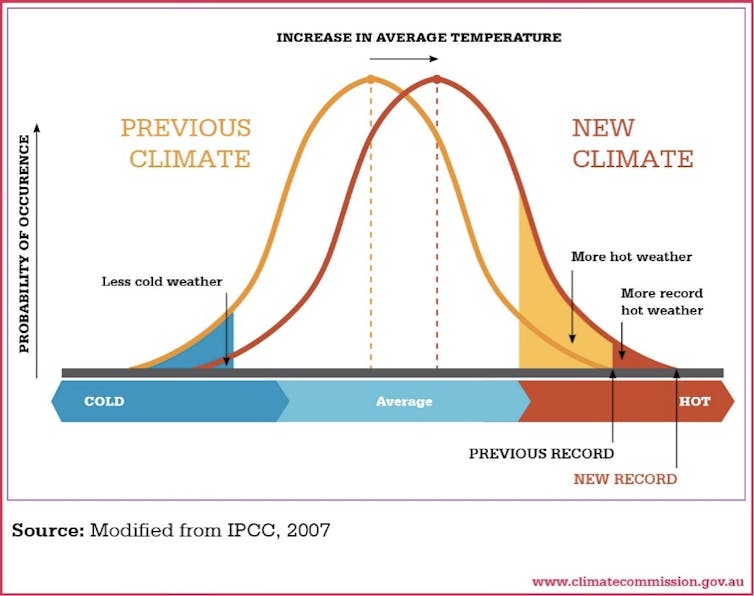

Climate scientists expect to see temperature records broken as our planet continues to heat up. This is because the distribution of possible temperatures is shifting higher and higher.

Australia Climate Commission/IPCC, CC BY-SA

Chile has already experienced the effects of climate change recently through a severe heatwave in February – late summer – resulting in several deaths from wildfires, as well as a decade-long mega-drought. The country recently rejected a rewrite of the constitution which would have mandated its government to take action against the nature and climate crises.

The longer-term impact of a winter heatwave

The hottest temperatures now appear to have largely subsided in the Andes. However, temperatures are still well above average for northern Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay, and will remain so for the next five days or so.

The impacts of winter heatwaves are less well understood than summer heatwaves. For Chile, the most likely impact is on snowpack in the mountains, which provides water for drinking, agriculture and power generation. Any melting of the snowpack will probably also affect the diverse flora and fauna found in the Andes.

Overall, this heatwave is a startling reminder of how humans are changing Earth’s climate. We will continue to see such unprecedented extremes until we stop burning fossil fuels and emitting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Matthew Patterson is a postdoctoral research assistant in atmospheric physics at the University of Oxford in the UK.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.