Saudi Arabia watered down a major UN climate science report by pushing for the use of unproven technologies that would allow the continued extraction of oil and gas, sources close to the negotiations have told Climate Home News.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s latest report focuses on how to halt global heating below 2C and to 1.5C in line with the Paris Agreement. While it deals with solutions, this is the most politically sensitive part of the IPCC’s three-part assessment.

Publication was delayed by six hours on Monday following a marathon 40-hour session over the weekend for scientists and government representatives to finalise its summary for policymakers – the longest approval plenary in the IPCC’s 34-year history.

The document concludes “a substantial reduction in overall fossil fuel use” is needed to tackle the climate crisis. But compared to earlier drafts, there is a much stronger emphasis on technologies to capture and store carbon dioxide underground (CCS) as a potential solution that extends the lifespan of coal, oil and gas infrastructure.

Saudi Arabia, one of the world’s largest oil producers and exporters, successfully argued for the repeated inclusion of references to CCS, which remains unproven at commercial scale. Opposition from European nations wasn’t enough to prevent a weakening of language on the need to phase out coal, oil and gas.

CCS and other carbon dioxide removal practices have become “the escape hatch for the fossil fuel industry,” one source told Climate Home. The negotiations are closed to media.

Five takeaways from the IPCC’s report on limiting dangerous global heating

Wrangling over this and other issues made the summary longer. In total, 22 pages were added compared to a draft dated 16 March seen by Climate Home News – taking it from 41 to 63 pages.

Language on risks and feasibility concerns about carbon dioxide removal techniques was toned down. References to shifting away from coal, oil and gas were qualified with the word “unabated” and “fossil fuels with CCS” was identified as a way to cut emissions in line with global climate goals.

A whole section was introduced on CCS, describing the technology as “an option” to cut emissions from fossil fuel use and in the industry sector. It notes that CCS has the capacity to store more carbon under ground that what is needed by 2100 to limit warming to 1.5C, albeit with some regional limitations.

And the report makes clear that CCS technology is the way to keep the oil and gas industry alive: “Depending on its availability, CCS could allow fossil fuels to be used longer, reducing stranded assets,” it states.

Saudi Arabia gets more than half its government revenue from the oil and gas sector. In recent years, the Kingdom has promoted the concept of a “circular carbon economy”, advocating for technological solutions that would cut emissions while allowing it to continue to extract and sell its oil for decades to come.

In the negotiations, Saudi Arabia was isolated on the issue. But its vocal position may have provided cover for others with similar views.

“The US was silent on CCS,” Teresa Anderson, climate justice lead at ActionAid International, told Climate Home. “It really seemed like they were happy to let Saudi Arabia be the bad guys.”

Anderson added: “The IPCC report delivers a clear warning that reliance on technofixes and tree plantations to solve the problem not only amount to wishful thinking, but would drive land conflicts and harm the food, ecosystems and communities already hardest hit by the climate crisis.”

The Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) denounced the outcome of the negotiations as “de-emphasising” the risks and uncertainty of carbon dioxide removal techniques while “overwhelmingly rely[ing] on technologies that pose grave threats to people and the environment”.

“States may water down the text but they cannot mask this clear scientific reality: only a rapid and equitable phaseout of fossil fuels, and the transformation of our energy system, can avoid overshooting 1.5C and the irreparable damage that would follow,” said Nikki Reisch, climate and energy programme director at CIEL.

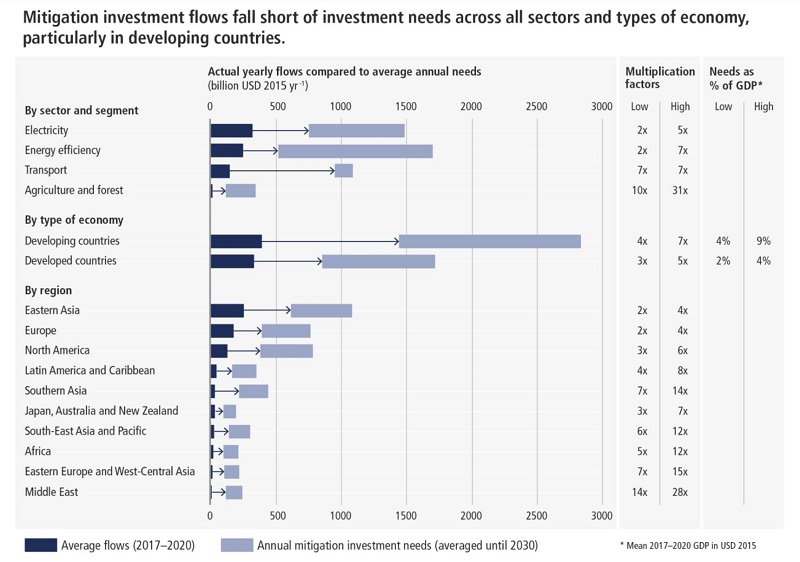

Breakdown of recent average (downstream) mitigation investment flows and modelled investment needs until 2030 in scenarios likely to limit warming to below 2°. The figure was deleted from the summary for policymakers after a dispute between the US and China (Source: draft IPCC WGIII report)

Another point of contention between the US and China was the scale of the funding gap for developing countries to cut emissions compared to wealthier ones.

The issue flared over a figure detailing the finance gap by sector and for developed and developing countries. It showed that developing countries need on average four to seven times more mitigation finance per year to 2030 to align with pathways that limit warming to below 2C – an upper range of approximately $2.8 trillion.

The US opposed the distinction between developed and developing countries in the graph – a red line for China. The figure was eventually deleted from the summary but remains in the underlying report.